Decoding and Targeting RNA Machines in health and disease

Since the beginning of life on earth, RNA molecules have taken the central stage due to its ability to simultaneously carry genetic information and catalyze chemical reactions. We are striving to understand the physical basis of RNA functions in biology and disease, and develop new RNA-based and RNA-targeting medicine. Current work in our lab spans the development of new chemical and computational tools, and their applications to gene regulation mechanisms, developmental biology, virus infections, genetic disorders, and RNA therapeutics.

1. Solving RNA 2D/3D/4D structurome and interactome in vivo.

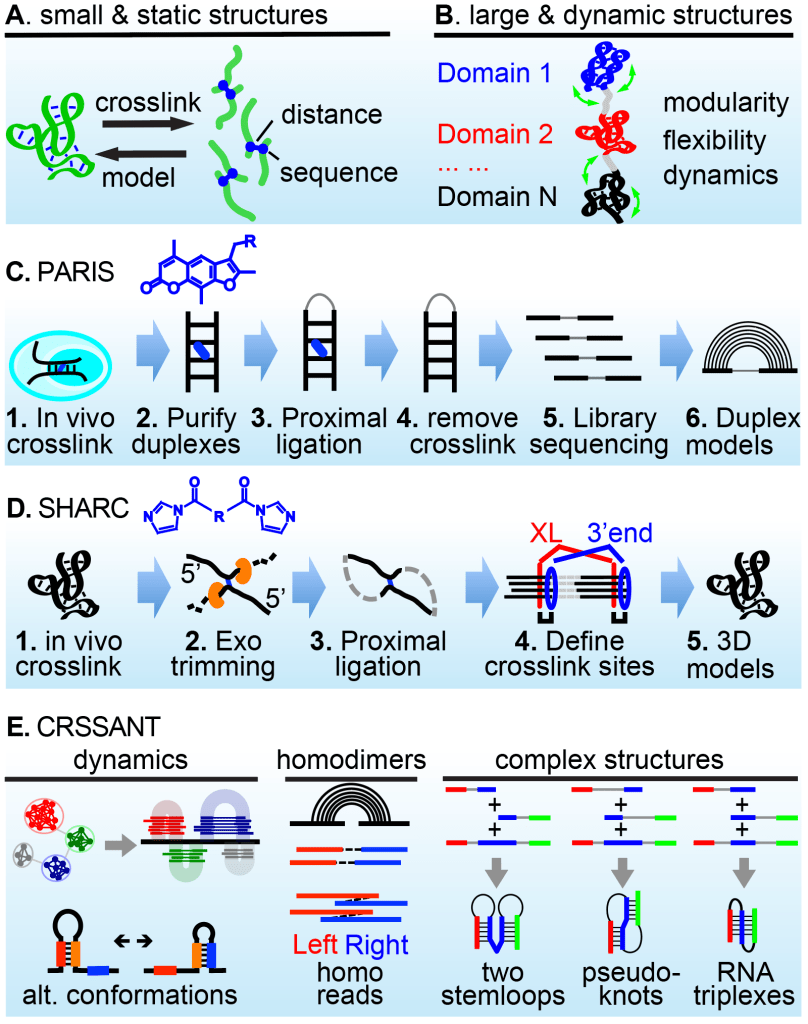

Despite tremendous progress in biophysical methods for RNA structure analysis, most cellular RNAs remain beyond reach. We developed a series of methods to directly solve RNA 2D/3D structuromes and interactomes in living cells at single-molecule level with base pair resolution, based on a simple mathematical intuition: the static 3D structure of any object can be determined by spatial distances among its subunits (Figure 1A), whereas complex and dynamic conformations can be deconvolved from such distances (Figure 1B). In PARIS, psoralen crosslinking, ligation and sequencing reveals global 2D structurome and interactome (Figure 1C). In SHARC, bifunctional acylation, exo trimming, ligation, sequencing and Rosetta modeling establishes 3D structures in vivo (Figure 1D). We further developed computational tools to classify and cluster contact information (CRSSANT), revealing a wide variety of complex and dynamic conformations in vivo, including helix combinations, pseudoknots, triplexes, and homodimers (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Solving RNA 2D/3D/4D structurome and interactome in vivo using chemical crosslinkers and computational modeling. (A-B) Principle: measuring distances to build RNA static and dynamic structures and interactions. (C) PARIS: psoralen crosslink-ligation pipeline for 2D structure / interaction analysis. (D) SHARC crosslink-trim-ligation for 3D structure / interaction analysis in vivo. (E) CRSSANT reveals dynamic and complex RNA conformation. See PARIS on the cover of Cell, and video in Youtube Get an Eye-full (Eiffel)).

Key publications:

Lu et al. 2016. Cell: PARIS for 2D structurome/interactome

Zhang et al. 2021 Nature Communications: PARIS2, >4000 fold better

Van Damme et al. 2022 Nature Commutations: SHARC for 3D structurome/interactome

Zhang et al. 2022 Genome Research: CRSSANT, computational tools

2. ncRNA interaction networks in development and disease

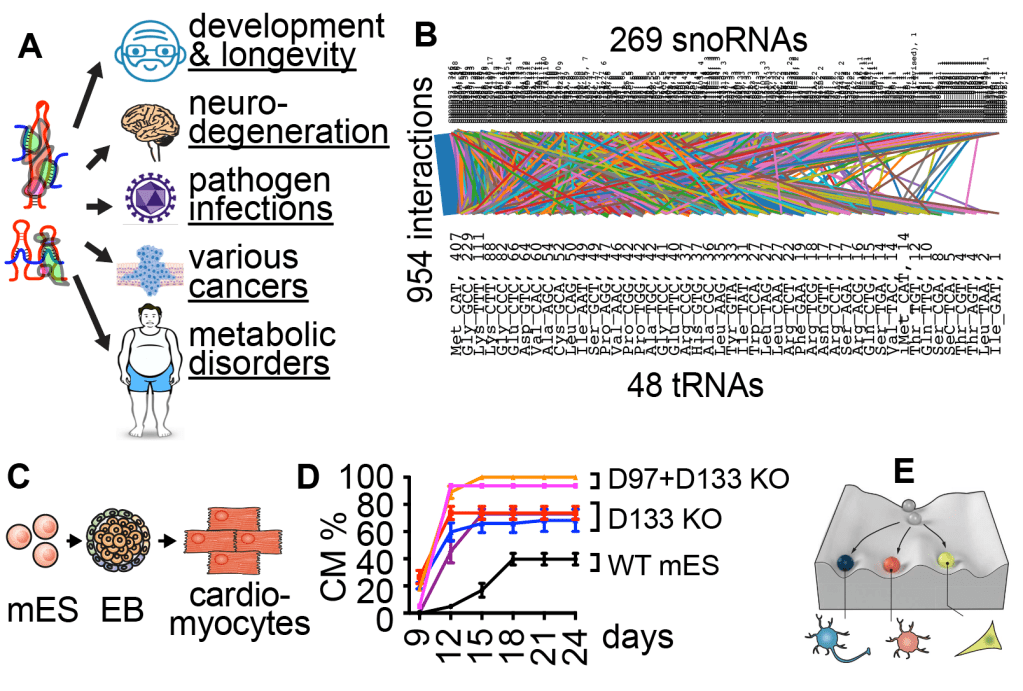

All life forms use a large variety of noncoding RNAs to regulate basic cellular processes. Except for a few examples, partners of most ncRNAs remain unknown. Our long term goal is to discover all RNA interaction networks in cells and determine their functions in normal and pathological states. Current focus includes snRNAs, snoRNAs, functional fragments of abundant ncRNAs such as tRNAs. In recent studies, we have discovered targets of a large number of snoRNAs, many of which are directly linked to genetic and infectious diseases (Figure 2A). For example, the neuro-developmental disorder Leukoencephalopathy with Calcifications and Cysts (LCC) is caused by mutations of the U8 snoRNA. We discovered that U8 interacts with other snoRNAs and 18S/28S rRNAs to form a network, which is disrupted by disease mutations. We further discovered an extensive snoRNA-tRNA interaction network that controls global tRNA modifications, stability, activity and codon-biased translation (Figure 2B). Loss of specific snoRNAs e.g., D97/D133 tips the balance between proliferation and animal development, dramatically accelerating differentiation of stem cells into the meso/endo-derm, such as cardiomyocytes (Figure 2C-E).

Figure 2. snoRNAs play critical roles in many human physiological and pathological conditions (A). We discovered >7000 snoRNA interactions, including a global snoRNA-tRNA network (B) that controls a embryogenesis, in particular cardiomyocyte differentiation (C-D), revealing new regulators of development (E).

Key publications:

Lu et al. 2016 Cell. U8-rRNA interaction network

Zhang et al. 2021 Nature Communications: U8 mutations in LCC

Zhang et al. 2022 Genome Research: U8 homodimer

Zhang et al. 2023 PNAS. snoRNA-tRNA network in stem cells

3. Decoding and targeting pre-mRNA structures in splicing

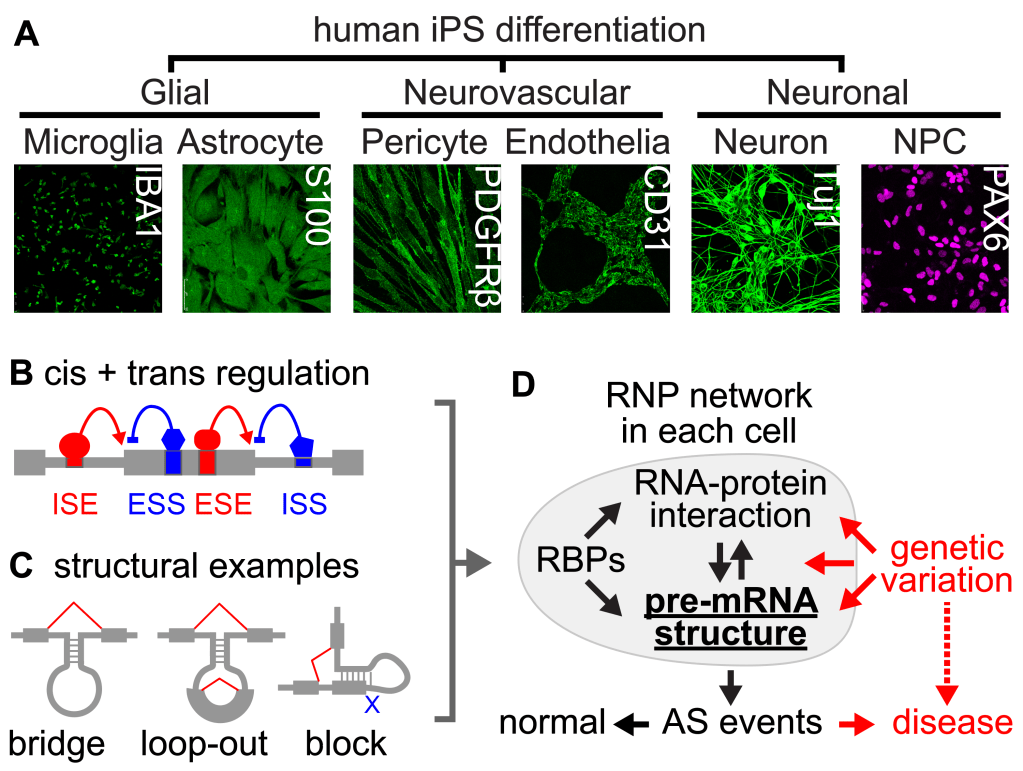

Alternative splicing (AS) is a major mechanism that generates the vast proteome diversity from the limited number of genes. Spatial and temporal regulation of AS contributes to cell differentiation and lineage determination (see iPS model, Figure 3A). It is estimated that up to a third of disease mutations impact splicing, causing neurodegeneration, muscular dystrophies, and cancer. In the past 3 decades, studies of AS have focused on 2 aspects: cis elements, including splice sites and regulatory motifs, and trans factors, like RNA binding proteins (RBPs) (Figure 3B). Thermodynamics dictate that cellular RNAs fold into low free energy structures within RNA-protein complexes (RNPs). In each RNP, RNA structures, RNA-RNA, RNA-protein, and protein-protein interactions form a dynamic network topology (instead of a static structure, Figure 3C). Little is known about how such pre-mRNP topologies, especially the dynamic RNA structures, control the cis+trans mechanisms of splicing. Building upon the iPS models and methods we developed, such as PARIS, SHARC, and CRSSANT, our long term goal is to determine the structural basis of splicing regulation and develop new RNA therapeutics for genetic disorders caused by splicing dysregulation.

Figure 3. Using the iPS neurodifferentiation system (A) to study splicing regulation by cis elements + trans factors (B) and structure (C). Analysis of RNP 3D topologies is key to understanding AS regulation under normal and disease states (D).

Key publications:

Garcia et al. 2013. RNA: splicing mechanisms in Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Lu et al. 2014. Genome Biology: snRNA-mRNA interactions

Zhang et al. 2021. Nature Communications: snRNA-mRNA interactions

4. Viral genome structures and host-viral RNA interactions

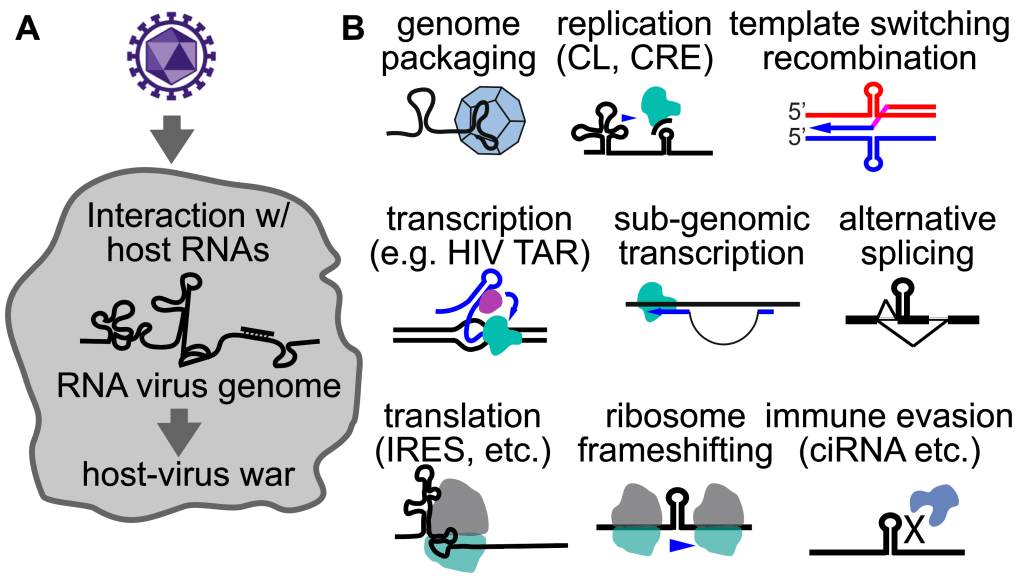

RNA viruses are existential threats to the human society. Their genomes directly participate in all steps of their life cycles by forming functional structures and interacting with host molecules, including host RNAs (Figure 4). Classical physical and chemical probing methods have made limited progress toward understanding these mechanisms. Our long-term goal is to build comprehensive structure and interaction models for RNA virus genomes and their transcripts in vivo, and use such information. to develop better anti-viral therapeutics. In recent studies, we have established the first global structure maps of several enteroviruses that cause paralysis in human patients (Zhang et al. 2021 Nature Comm.), revealing dynamic conformations that response to antivirals and regulate IRES translation.

Figure 4. The never-ending war between hosts and viruses (A), and the diverse functions of viral RNA structures and their interactions with host transcriptomes (B).

Key publications:

Zhang et al. 2021. Nature Comm. Enterovirus genome structures

5. Structural and functional modularity of large RNAs

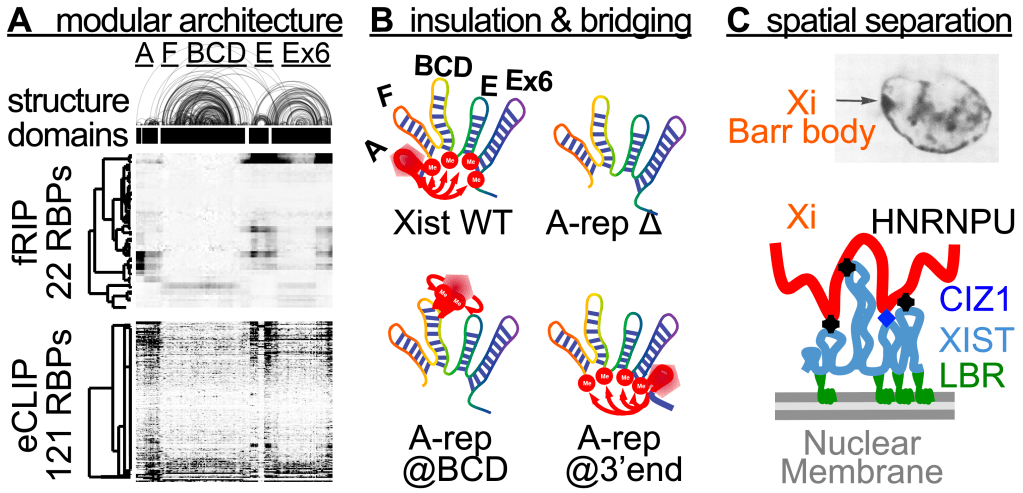

Large RNA molecules, both coding and noncoding, often carry complex biological functions. The organization of their structures and functions are almost impossible to study using conventional physical methods. Application of our in vivo structure analysis tools such as PARIS revealed high level structural and functional organizations of these large RNAs. For example, XIST, a founding member of the lncRNA family, controls the inactivation of an entire X chromosome in placental mammals by recruiting multiple proteins to deposit epigenetic modifications, remodel the X chromosome, and silence transcription in specific nuclear compartment (Lu et al. 2016 Cell. Lu et al. 2017 Phil. Trans.). Our work revealed a modular architecture that determines binding specificity of its protein partners (Figure 5A), controls m6A modification patterns through spatial insulation and bridging (Figure 5B), and enables separation of domains that tether the inactive X chromosome (Xi) to the nuclear periphery as the Barr body (Figure 5C, Lu et al. 2020 Nature Comm.). This approach is broadly applicable to all large RNAs that can not be studied in test tubes.

Figure 5. Structural and functional modularity of large RNAs, e.g., XIST. (A) PARIS derived 2D structure of XIST correlate with RBP binding patterns from fRIP and eCLIP. (B) The 5 domains controls m6A specificity through spatial insulation and bridging. (C) The 3D topology of the XIST RNP complex enables tethering of Xi to the nuclear membrane

Key publications:

Lu et al. 2016. Cell. XIST 2D structure

Lu et al. 2017. Phil. Trans. X chromosome inactivation and XIST

Lu et al. 2020. Nature Communications. Topology of XIST, MALAT1 and NEAT1 RNPs

6. A new class of tRNA intronic circular (tric)RNAs

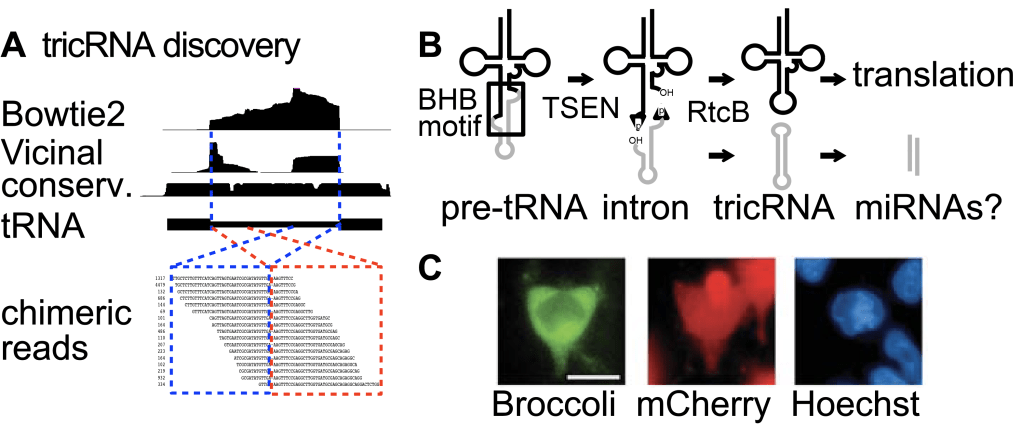

Standard sequencing and analysis methods can only be used to study typical linear RNAs. We developed computational tools, such as Vicinal that can define RNA ends and topologies from various sequencing data (Lu and Matera 2014). Using Vicinal, we discovered a unique new class of circular RNAs produced from tRNA splicing, termed tricRNAs (tRNA intronic circular RNAs, Figure 6A). We defined the factors required for tricRNAs biogenesis using biochemistry and fly genetics (Figure 6B). Some of the tricRNAs are further processed to generate miRNA-sized products with potential new functions. Based on the simplicity and ubiquity of tricRNA biogenesis, we designed a system for efficient production of circular RNAs in living cells (Figure 6C). This expression system has a wide range of potential applications, from basic research of circular RNA biology to pharmaceutical science, such as in vivo expression of fluorescent RNAs, and delivery of RNA-based therapeutics (Lu et al. 2015 RNA).

Figure 6. Discovery and application of tricRNAs. (A) The Vicinal method. (B) tricRNA biogenesis mechanism and potential function as miRNA precursor. (C) tricRNA as vector to express the fluorescent Broccoli RNA in living cells.

Key publications:

Lu et al. 2015. RNA: tricRNA discovery and application

Lu and Matera. 2014. Nucleic Acid Research: Vicinal computational method